The I Ching does not offer itself with proofs and results; it does not vaunt itself, nor is it easy to approach. Like a part of nature, it waits until it is discovered. It offers neither facts nor power, but for lovers of self-knowledge, of wisdom – if there be such – it seems to be the right book

– C.G Jung

Perceive that which cannot be seen with the eye

– Miyamoto Musashi

According to Chung-Ying Cheng in The Primary Way, the I Ching advanced with the contribution of Confucius. No one disputes the I Ching began as a divinatory system. There is some disagreement about the philosophy of the book, if it exists, and about the role of Confucius.

Everyone finds their own way with the I Ching so it’s not really possible to say it’s one thing not another. Read Thomas Cleary’s Buddhist I Ching and it’s Buddhist. Read his Taoist I Ching, and it’s Taoist. There is however a traditional culture which mostly traces back to Wilhelm. His book was a great achievement because it is poetic, above and beyond divinatory advice.

Wilhelm explains the connection between the Ten Wings and the rest of the book, which means a juxtaposition of Confucianism with Taoism. The numerology, symbols and trigrams are Taoist, like a painting of rivers and mountains. The exposition, some of it, has a Confucian flavour.

One way of understanding this is to think in terms of art and what you say about it, as two different things. In Tao The Chinese Philosophy of Time and Change (Rawson, Legeza) there are diagrams and symbols of change and energy:

In Taoist art the two chief groups of imaginative unit are first: cyclic patterns of process; and second; linear threads or veins. the obvious examples of these are, first: the trigrams of the I Ching oracle book, with their seasonal and directional significance; and second; the continuous mobile brush line in painting.

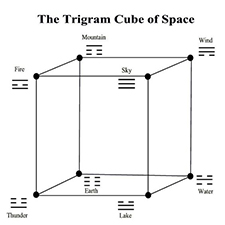

The flow of ch’i, cycle of seasons, weather and time, are visually suggested in a Taoist painting. It is equally apparent in the I Ching, although with abstract simplicity. The abstraction is mathematically significant. The six lines of a hexagram correspond to a cube, representing the space of matter.

You need guidance reading the trigrams and hexagrams, which derives from the Shuo Kua. Without that part of the Ten Wings, no one in the West would have understood trigrams. You internalise the meanings with experience, based on the work of others. Meaning occurs when symbol and text relate. A painting of a mountain remains the same. How you interpret the painting varies according to the person, moment, and feeling.

For some years I read Wilhelm’s book thinking it was Taoist, not understanding the Confucian influence. The labels are of no consequence, but I was thinking differently. Harmony for Confucius is sociological, but you can see it as simultaneously Taoist. In the Tao Te Ching Lao Tsu appears to dismiss social problems, but that’s not the rationale of his book. He means the material world is not where you find spirit, essence, or self; that you release the first to discover the latter.

According to Chung-Ying Cheng, the social and spiritual difference is resolved when you recognise a vertical reality within horizontal struggle. How you act and decide has consequences within a greater system:

Correct understanding and correct action are not always conducive to one’s immediate advantage or interest, but nevertheless they will always contribute to one’s total growth as a person. One must also note that to act according to one’s circumstances is not to act without principle; on the contrary, it is to act with a principle that will bring out the harmony and unity in the circumstances (The Primary Way).

In another passage, Cheng expands this idea with the notion of theory and action:

The process of self-cultivation involves both correct understanding (theory) and correct practice (action). Valid self-cultivation is always found in the unity of theory and practice, and understanding and action. Hence, to sustain harmony and unity in oneself, one must achieve unity of understanding and action. But there will be no unity if there is no correct understanding of one’s position and relationship with others in the world, and there will be no unity if there is no correct action following correct understanding.

Chung-Ying Cheng is complicated but provides useful philosophy. Taoism is simple and hard to define, in relation to which Aikido philosophy is more direct. In Aikido and the Dynamic Sphere, Adele Westbrook and Oscar Ratti describe centring as the important consideration. Chinese arts speak of the tan-tien as the psychophysical basis for movement. Japanese arts speak of hara, which is essentially the same:

This centre will be used as a unifying device in the difficult process of co-ordinating the whole range of your powers and possibilities. It will be used in establishing a stable platform of unification and independence from which you may operate in full control, relating to and coping with your reality.

These ideas are a structure for living, for which the I Ching is a manual, advising on understanding and action. There is a vertical reality which is philosophical, and a horizontal which is practical. As human beings we reflect nature in terms of yin, yang, and eight qualities. As with the elements, more correctly described as phases: “The eight trigrams therefore are not representations of things as such but of their tendencies in movement” (Wilhelm).

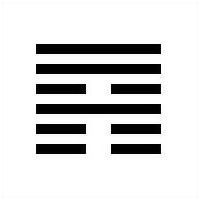

The question when you throw the coins is this: where is your position? Hexagram 53 for example is called Development or Gradual Progress. This is relative. Every person is different which means varying answers according to circumstance and level. Wilhelm describes it poetically: “This hexagram is made up of Sun (penetration) above, i.e., without, and Kên (stillness) below, i.e., within. A tree on a mountain develops slowly according to the law of its being and consequently stands firmly rooted.”

I write like this is a magazine column. With research, references, and a lot of time. If you like it, perhaps you would support me.